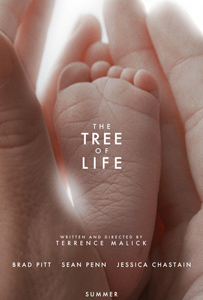

Critics Don’t Get “Tree of Life”

By Jack Cashill

AmericanThinker.com - June 25, 2011

C

ritics know they are supposed to like Terrence Malick, the reclusive auteur who has made just five films over the course of his 40-year career. His movies from the 1973 Badlands to the 2011 Tree of Life are all distinctive, bold and beautifully shot.

What Malick does not do is give interviews. As a result, the better critics impose their own philosophical template on what they see, and the lesser ones crib from the better ones. This works well enough for Malick’s more terrestrial films, but for the deeply spiritual Tree of Life, it does not work well at all.

The problem is that most film critics no longer know enough about our Biblical legacy to review a movie about faith. Salon’s Andrew O’Hehir, for intance, calls the film “a crazy religious allegory.” Why crazy? The Village Voice’s Nick Pinkerton fills in the details: the characters actually address “the gauche subject of the eternal” and do so in a quaint “Judeo-Christian lingua franca.” Imagine that!

“There are two ways through life: the way of nature, and the way of grace. You have to choose which one to follow.”

Pinkerton betrays his theological cluelessness in his summary of the film: “Though markedly faithful to Darwin, Malick’s film begins with a quotation from the Book of Job, imagines heaven, and features Mother pointing to the sky to deliver the lesson: ‘God lives there.’”

Markedly faithful to Darwin? No, Nick, the film is a pie in Darwin’s face. The quotation from Job reads as follows, “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? . . .What supports its foundations, and who laid its cornerstone as the morning stars sang together and all the angels shouted for joy?"

In the film, this epigraph is followed by an extended visual imagining of the creation of life on earth. The fact that Malick uses imagery pulled from the Hubble Telescope and the like does not make it Darwinian.

Indeed, in the cited passage God chides Job for daring to think that he, like Darwin, knows how life on earth began. The fact that Malick uses spiritual music throughout the sequence, some of it Gregorian, should have been a clue that blind chance and natural selection were not exactly at play here.

Indeed, in the cited passage God chides Job for daring to think that he, like Darwin, knows how life on earth began. The fact that Malick uses spiritual music throughout the sequence, some of it Gregorian, should have been a clue that blind chance and natural selection were not exactly at play here.

The end product of creation, rendered in the film as one example out of millions, is the O’Brien family of 1950’s Waco, Texas. The mother, father and three pre-adolescent sons face the challenge that all humanity faces as voiced by the ethereal Mrs. O’Brien, “There are two ways through life: the way of nature, and the way of grace. You have to choose which one to follow.”

This quote marks an interesting contrast with the opening quote of the Calvinist True Grit: “ There is nothing free except the Grace of God. You cannot earn that or deserve it." The O’Brien family is Catholic, and the film more or less reflects their Catholicism. That two high profile Hollywood products could open the door on a theological debate is no minor miracle in itself.

As evoked through the memory of her now fiftyish son (Sean Penn in the film, the loving and forgiving mom (Jessica Chastain) would seem to represent the way of grace, the stern and demanding dad (Brad Pitt) the way of nature. It is the father who teaches his sons to box and to make their way in a business world that is less than fair.

Most critics, secular and otherwise, accept this dichotomy. Jay Michaelson, a “religious progressive,” is one of them. Not surprisingly, he does not much like Mr. O’Brien whom he considers “violent, petty, and regretful,” a contemporary reflection of the “macho sky-god of the oxymoronic ‘Religious Right.’”

If the religious left has any higher calling than to take cheap shots at the religious right, I have yet to discover it. Michaelson blunders on, “Is life, as our contemporary conservatives tell us, merely a competition of natural drives, dog-eat-dog, live-and-let-die? Surely one could think so; nature is indeed ruthless.” Who are these conservatives? Donald Trump?

Yes, nature is ruthless. In the creation sequence, we watch as one dinosaur casually steps of the head of a wounded fellow critter. In contemporary Waco, the O’Brien’s rebellious eldest son Jack leads his friends on a mini-orgy of vandalism, which culminates in his tying a frog to a roman candle and shooting it into space.

When dad is away on business, Mrs. O’Brien indulges her sons, and the house descends into amiable anarchy. When a neighborhood of dads is permanently absent, as has happened in so many of America’s cities, the way of nature prevails, and Jack O’Brien’s little posse becomes the Crips.

Malick spares us the psycho authoritarian dad of American Beauty and too many other contemporary movies. Mr. O’Brien loves his sons and is not afraid to show it. He can be harsh, but he is always rational, and he does not hit his children.

The one bit of violence occurs when Mrs. O’Brien, angry after one of her husband’s outbursts, tries to hit him. He grabs her arm, restrains her, then holds her in a loving embrace. No critic I read mentioned this scene. It is the most telling one in the movie.

Grace, like life, comes through the union of a man and a woman. As Job did, Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien struggle together imperfectly to make sense of a world that defies easy understanding. The payoff, as Malick suggests, comes only at life’s end.

“I won't discuss the end of the film,” says a patronizing O’Hehir, “but implausible as this may sound, ‘The Tree of Life’ may appeal to more adventurous Christian viewers.”

In the above sentence, I would substitute “secular” for “Christian.” It is the secularists whose faith this film will test.